Education and Early Career

Robert Mundell's educational journey and early career laid the foundation for his groundbreaking contributions to international economics. He began his higher education at the University of British Columbia, where he earned a bachelor's degree in 1953 with a joint major in economics and Slavonic studies. This unique combination of disciplines foreshadowed Mundell's future ability to approach economic problems from diverse perspectives.Following his undergraduate studies, Mundell pursued graduate work at several prestigious institutions. He spent a year at the University of Washington in Seattle before moving to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he was influenced by renowned economists Paul Samuelson and Charles Kindleberger. Seeking to broaden his international exposure, Mundell then spent a year at the London School of Economics (LSE), attracted by the work of Lionel Robbins and James Meade.

At LSE, Mundell completed his Ph.D. thesis on international capital movements under the supervision of James Meade, who had recently published pioneering books on international economic policy theory. This work, completed in 1956, set the stage for Mundell's future contributions to international economics.

After obtaining his doctorate, Mundell was awarded a post-doctoral fellowship at the University of Chicago in 1956-57, further honing his skills and expanding his network in the economics community. His early career saw him teaching at various institutions, including the University of British Columbia, Stanford University, and the Johns Hopkins Bologna Center of Advanced International Studies in Italy.

It was during this period that Mundell began publishing influential papers on international trade, optimum currency areas, and monetary and fiscal policy trade-offs under fixed and floating exchange rates. These early works caught the attention of Jacques Polak, then head of the International Monetary Fund's Research Department, leading to Mundell's recruitment to the IMF in 1961.

Mundell's two-year stint at the IMF (1961-63) proved crucial for his intellectual development. One of his first assignments was to address the problem of the appropriate mix of fiscal and monetary policy, a topic that was being hotly debated with respect to the United States. This work resulted in groundbreaking papers that would later form the basis of the Mundell-Fleming model, a cornerstone of international macroeconomics.

This early period of Mundell's career, characterized by a diverse educational background and exposure to various academic and institutional environments, set the stage for his future contributions that would revolutionize the field of international economics and earn him the Nobel Prize in 1999.

Academic Positions and Roles

Throughout his illustrious career, Robert Mundell held numerous prestigious academic positions that allowed him to shape economic thought and influence generations of students and policymakers. After his initial teaching experiences at various institutions, Mundell secured a position as a professor of economics at the University of Chicago from 1966 to 1971. During this time, he also served as the editor of the Journal of Political Economy, one of the most respected publications in the field.Mundell's time at the University of Chicago was particularly significant, as it coincided with a period when the institution was home to several future Nobel laureates and influential economists. His teaching style was described as both stimulating and challenging, with Michael Mussa noting that Mundell liked to pose "intelligent questions that weren't entirely well structured and therefore didn't have clear answers". This approach helped cultivate critical thinking skills in his students, many of whom went on to become prominent economists themselves.

In addition to his role at Chicago, Mundell held summer professorships at the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva from 1965 to 1975. This position allowed him to maintain strong connections with European economic thought and policy, which would prove crucial in his later work on optimal currency areas and the euro.

In 1974, Mundell joined the faculty at Columbia University, where he would remain for the rest of his career. At Columbia, he was eventually awarded the university's highest academic rank of University Professor, a testament to his contributions to the field and his institution.

Mundell's academic roles extended beyond traditional university settings. He was a consultant to numerous international organizations, including the United Nations, the IMF, the World Bank, and the European Commission. These roles allowed him to bridge the gap between academic theory and practical policy implementation, enhancing his influence on global economic affairs.

In his later years, Mundell also held positions at institutions in Asia, reflecting the growing importance of the region in the global economy. He was appointed as the Distinguished Professor-at-Large of The Chinese University of Hong Kong, further expanding his global influence.

Throughout his career, Mundell organized yearly academic conferences on pressing economic issues, a tradition he began in the early 1970s. These conferences, often held at his Italian villa, became important forums for discussing and debating economic ideas, bringing together leading economists and policymakers from around the world.

Mundell's diverse academic roles and positions allowed him to shape economic thought on an international scale, influencing both theoretical developments and practical policy implementations across multiple continents and generations of economists.

Nobel Prize and Achievements

Robert Mundell's groundbreaking contributions to international economics culminated in his receipt of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1999. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded him the prize "for his analysis of monetary and fiscal policy under different exchange rate regimes and his analysis of optimum currency areas".Mundell's work on optimum currency areas, developed in the early 1960s, laid the theoretical foundation for the creation of the euro. His insights into the conditions under which countries could benefit from sharing a common currency proved prescient, as the European Union moved towards monetary integration in the late 20th century. This work earned him the moniker "father of the euro".

One of Mundell's most significant achievements was the development of the Mundell-Fleming model, which extended the IS-LM framework to open economies. This model became a fundamental tool for analyzing the effectiveness of monetary and fiscal policies under different exchange rate regimes. It demonstrated that the choice of exchange rate system significantly impacts the efficacy of macroeconomic policies, a insight that continues to influence policymaking today.

In addition to his theoretical work, Mundell made important practical contributions to international monetary policy. He served as an adviser to numerous international organizations, including the United Nations, the IMF, the World Bank, and the European Commission. His expertise was sought by governments around the world, allowing him to directly influence economic policy on a global scale.

Mundell's work on supply-side economics in the 1970s also had a significant impact. His advocacy for tax cuts and flattening of income tax rates influenced economic policy debates, particularly in the United States. While controversial, these ideas contributed to a broader reassessment of the role of taxation in economic growth.

Throughout his career, Mundell demonstrated an "uncommon—almost prophetic—accuracy in predicting the future development of international monetary arrangements and capital markets". His ability to foresee economic trends, such as the stagflation of the 1970s, further cemented his reputation as a visionary economist.

The Nobel Prize was a crowning achievement in a career marked by numerous honors. Mundell received the Guggenheim Prize in 1971, the Jacques Rueff Medal and Prize in 1983, and was made a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1998. These accolades reflect the profound impact of his work on the field of economics and its practical applications in global finance and policy.

Mundell-Fleming Model Impac

The Mundell-Fleming model, developed independently by Robert Mundell and Marcus Fleming in the early 1960s, has had a profound impact on international macroeconomics and policy analysis. This model extends the IS-LM framework to open economies, providing crucial insights into the interactions between monetary and fiscal policies, exchange rates, and international capital flows.

One of the model's most significant contributions is the concept of the "impossible trinity" or "trilemma," which posits that a country cannot simultaneously maintain a fixed exchange rate, free capital movement, and an independent monetary policy. This principle has become a cornerstone of international economic policy analysis, influencing central banks and policymakers worldwide in their approach to managing open economies.

Comparative static analysis

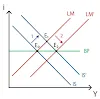

The graphs below summarize the results of comparative static analysis through the Mundell-Flaming model

In terms of policy implications, the Mundell-Fleming model demonstrates that the effectiveness of monetary and fiscal policies depends crucially on the exchange rate regime:

* Under a floating exchange rate system, monetary policy is highly effective in influencing output, while fiscal policy is relatively ineffective.

* Conversely, under a fixed exchange rate system, fiscal policy becomes more potent, while monetary policy loses its effectiveness.

These insights have been instrumental in shaping economic policies, particularly for small open economies facing the challenges of globalization and international capital flows.

The model has also been influential in academic circles, becoming a standard component of international economics curricula. Its ability to explain complex economic phenomena in a relatively simple framework has made it an enduring tool for both theoretical and applied economic analysis.

However, like all models, the Mundell-Fleming framework has limitations. It assumes perfect capital mobility and static exchange rate expectations, which may not always hold in reality. Despite these limitations, the model's core insights continue to provide valuable guidance for understanding the macroeconomic dynamics of open economies in an increasingly interconnected world.

Optimal Currency Regions

The Optimum Currency Area (OCA) theory, pioneered by Robert Mundell in 1961, provides a framework for evaluating the economic viability of a region adopting a single currency. This theory is particularly relevant in understanding the economic foundations of monetary unions like the Eurozone.Key criteria for an OCA include:

1. Factor mobility: Particularly labor mobility, which allows for adjustment to asymmetric shocks without the need for exchange rate adjustments.2. Price and wage flexibility: This enables regions to adjust to economic disturbances without causing high unemployment or inflation.

3. Economic openness: Regions with high trade integration are more likely to benefit from a common currency.

4. Product diversification: Economies with diverse production structures are better equipped to handle sector-specific shocks.

5. Fiscal integration: The ability to transfer funds between regions can help mitigate the effects of asymmetric shocks.

6. Political integration: A shared political will is crucial for maintaining a currency union in the face of economic challenges.

The theory suggests that when these criteria are met, the benefits of a common currency (such as reduced transaction costs and exchange rate uncertainty) outweigh the costs (like the loss of independent monetary policy).

However, the OCA theory has faced criticism and refinement over time. Some economists argue that the criteria for an OCA might be endogenous – that is, countries may become more suitable for a currency union after joining one, rather than before.

The Eurozone serves as a prime case study for OCA theory. While it meets some criteria, such as economic openness and product diversification, it falls short in areas like labor mobility (due to language and cultural barriers) and fiscal integration. These shortcomings have been highlighted during economic crises, particularly the European debt crisis of 2009-2012.

Despite its limitations, OCA theory remains a crucial tool for policymakers and economists in evaluating the potential costs and benefits of monetary integration, providing a theoretical foundation for understanding the challenges and opportunities of currency unions.

Mundell's Policy for the Success of the Euro

Robert Mundell, known as the "father of the euro," proposed several key policies for the success of the European single currency based on his theory of optimum currency areas. While advocating for labor mobility, fiscal integration, and central bank independence, Mundell later opposed the creation of a centralized fiscal authority for the eurozone, highlighting the complex challenges in balancing economic integration with national sovereignty.Labor Mobility and Fiscal Integration

Robert Mundell's theory of optimum currency areas emphasized the importance of labor mobility and fiscal integration as crucial factors for the success of a common currency like the euro. He argued that high labor mobility across member states would serve as an essential adjustment mechanism in the face of asymmetric economic shocks.Labor mobility allows workers to move freely between countries experiencing different economic conditions, helping to balance labor markets and reduce unemployment disparities. This mobility acts as a "safety valve" for regions facing economic downturns, as workers can relocate to areas with better job prospects. However, Mundell acknowledged that labor mobility within the eurozone has remained limited compared to other currency unions like the United States, due to linguistic, cultural, and administrative barriers.

Regarding fiscal integration, Mundell initially advocated for a degree of fiscal transfers between member states to help mitigate the impact of asymmetric shocks. This could involve a system where economically stronger countries provide financial support to weaker ones during times of crisis. Such a mechanism would help distribute risks across the currency area and enhance its overall stability.

However, the implementation of fiscal integration in the eurozone has been challenging. The European sovereign debt crisis of 2009-2015 highlighted the limitations of the existing framework, as the original European Monetary Union policy included a no-bailout clause. This clause proved unsustainable during the crisis, leading to ad hoc measures and debates about the need for more extensive risk-sharing policies.

Despite these challenges, Mundell remained a strong supporter of the euro, arguing that its benefits outweighed the costs. He believed that over time, the eurozone would develop the necessary institutions and mechanisms to address these issues, including potentially greater fiscal coordination and integration. However, he also cautioned against excessive centralization of fiscal powers, emphasizing the need to balance economic integration with national sovereignty.

European Central Bank Independence

Robert Mundell's vision for the euro included a strong emphasis on central bank independence, which was realized in the establishment of the European Central Bank (ECB). The ECB's independence was seen as crucial for maintaining price stability and credibility in the new currency union.Mundell argued that an independent central bank would be better positioned to resist political pressures and maintain a consistent monetary policy focused on long-term economic stability. This principle was enshrined in the Maastricht Treaty, which established the ECB and granted it a high degree of autonomy.

The ECB's primary mandate is to maintain price stability, defined as keeping inflation rates below, but close to, 2% over the medium term. This clear and narrow focus on price stability reflects Mundell's belief that monetary policy should be decentralized and focused on maintaining the value of the currency.

However, the ECB's role has evolved over time, particularly in response to crises. During the European sovereign debt crisis, the ECB took on a more expansive role, implementing unconventional monetary policies such as quantitative easing. This expansion of the ECB's toolkit has led to debates about the extent of its mandate and the balance between monetary and fiscal policy in the eurozone.

Mundell's work on optimal currency areas suggested that monetary policy alone might not be sufficient to address asymmetric shocks within a currency union. This insight has been borne out in the eurozone's experience, where the ECB's "one-size-fits-all" monetary policy has at times struggled to address divergent economic conditions across member states.

Despite these challenges, the ECB's independence remains a cornerstone of the euro's institutional framework. Mundell's emphasis on central bank autonomy continues to influence discussions about the future of Economic and Monetary Union, particularly as policymakers grapple with the need for greater economic coordination while preserving the ECB's credibility and independence.

Exchange Rate Stability and Reforms

Mundell argued that fixed exchange rates within a currency area would eliminate exchange rate uncertainty, reduce transaction costs, and promote price transparency across member states. This stability would encourage greater trade and investment flows, fostering deeper economic integration. However, he recognized that giving up independent monetary policy and exchange rate flexibility could pose challenges for countries facing asymmetric economic shocks.

To address these challenges, Mundell proposed several reforms and policy measures:

1. Enhanced labor mobility: Mundell stressed the need for increased labor mobility within the eurozone to serve as an adjustment mechanism in the absence of exchange rate flexibility. This would allow workers to move from areas experiencing economic downturns to those with better prospects, helping to balance labor markets across the currency area.

2. Price and wage flexibility: In the absence of exchange rate adjustments, Mundell emphasized the importance of flexible prices and wages to facilitate economic adjustments within the currency union. This would help countries regain competitiveness without resorting to currency devaluation.

3. Financial market integration: Mundell advocated for deeper financial market integration within the eurozone to promote risk-sharing and smooth out economic fluctuations. This would involve creating a more unified banking system and capital markets union.

4. Structural reforms: To enhance the resilience of individual economies within the currency union, Mundell recommended implementing structural reforms to improve economic flexibility and competitiveness. These reforms could include labor market liberalization, product market reforms, and measures to enhance productivity.

5. Fiscal coordination: While opposing a centralized fiscal authority, Mundell recognized the need for some degree of fiscal coordination among member states to ensure the stability of the currency union. This could involve agreeing on common fiscal rules and guidelines to prevent excessive deficits and debt accumulation.

Mundell's ideas on exchange rate stability and accompanying reforms have been influential in shaping the euro's institutional framework. However, the eurozone's experience has also revealed the challenges of implementing these reforms in practice, particularly in the face of diverse economic and political conditions across member states. The ongoing debates about further integration and reform within the eurozone continue to be informed by Mundell's insights on optimal currency areas and the trade-offs involved in maintaining a common currency.

Opposition to Central Fiscal Authority

Despite his advocacy for fiscal integration within the eurozone, Robert Mundell later expressed strong opposition to the creation of a centralized fiscal authority for the European Union. This stance, which may seem paradoxical given his earlier work on optimal currency areas, reflects Mundell's evolving views on the balance between economic integration and national sovereignty.In 2014, Mundell explicitly voiced his concerns about proposals for a fiscal union between European states. He declared that "it would be insane to have a central European authority that controls all the taxes and duties of the states ... controlled in the Union. This transfer of sovereignty is far too big". This statement underscores Mundell's belief that while some degree of fiscal coordination is necessary for a currency union, complete centralization of fiscal powers would be detrimental.

Mundell's opposition to a central fiscal authority stemmed from several considerations:

1. Preservation of national sovereignty: He believed that fiscal policy, including taxation and spending decisions, should remain primarily under the control of individual member states to reflect their unique economic conditions and political preferences.

2. Concerns about moral hazard: Mundell worried that a centralized fiscal authority might lead to excessive risk-taking by individual countries, knowing that the costs would be shared across the union.

3. Diversity of economic structures: Given the significant differences in economic structures and cycles among eurozone countries, Mundell argued that a one-size-fits-all fiscal policy would be ineffective and potentially harmful.

4. Political feasibility: He recognized the political challenges of convincing member states to cede substantial fiscal powers to a supranational authority.

Instead of a centralized fiscal authority, Mundell advocated for a system of fiscal coordination and discipline among member states. He supported the idea of common fiscal rules and guidelines to prevent excessive deficits and debt accumulation, but without transferring full fiscal sovereignty to the EU level.

Mundell also opposed the prospect of countries being liable for other countries' debt within the eurozone. This position aligns with his view that while some risk-sharing mechanisms are necessary for a currency union, they should not extend to full mutualization of debt, which could create perverse incentives and undermine fiscal discipline.

Despite these reservations about fiscal centralization, Mundell remained a strong supporter of the euro and European monetary integration. He believed that the benefits of a common currency, such as reduced transaction costs and increased price transparency, outweighed the challenges of coordinating fiscal policies across diverse economies. However, his opposition to a central fiscal authority highlights the ongoing debate about the optimal degree of integration within the eurozone and the complex trade-offs involved in balancing economic efficiency with national sovereignty.